[Editor’s note: Veteran Toronto Pursuits leader and arts writer Betty Ann Jordan is eager to take on the issue of women’s under-representation in the arts with participants, and keen to highlight the possibilities for change. We hope you will join her for this eye-opening week of women and the arts.]

In 1928, Virginia Woolf was invited by several women’s colleges at Cambridge University to deliver an address on “Women and Fiction.” The talk was later published as A Room of One’s Own. This text begins with the narrator, Woolf’s alter-ego Mary Burton, recalling how she was prevented from walking on the grass by a Cambridge beadle, who chased her off with the admonition, “Only the Fellows and scholars are allowed here.” Next she is denied access to the Trinity College library where she had thought to examine a manuscript; barring the entrance, an attendant insists that “ladies are only admitted if accompanied by a Fellow of the college or furnished with a letter of introduction.” These indignities are followed by a substandard dinner in the women’s residence, commencing with a deplorable plain gravy soup which she grimly dismisses, saying, “There was nothing to stir the fancy in that.”

Such was an ambitious female’s lot in a man’s world. Spurred by these mundane but telling experiences, Woolf is compelled to expand her inquiry to address the limitations experienced by women who had long been relegated to the status of “angels in the house.” It comes to her that several prerequisites could bring women into the fullness of their literary potential, namely a fixed annual income of five hundred pounds and a room of one’s own with a lock on the door. All material barriers to self-expression would be removed, with tremendous consequences. Woolf explains, “If we live another century or so … and have 500 pounds a year each of us and rooms of our own; if we have the habit of freedom and the courage to write exactly what we think; if we escape a little from the common sitting-room and see human beings not always in relation to each other but in relation to reality; then the opportunity will come.”

Woolf’s luxuriantly conversational essay is famous for an an extended flight of fancy in which she bemoans the plight of Shakespeare’s brilliant but thwarted imaginary sister who shared his talent but not, tragically, his gender. Laments Woolf, “She died young—alas, she never wrote a word. Now my belief is that this poet still lives in you and in me, and many other women who are not here tonight for they are washing up the dishes and putting the children to bed. But she lives; the great poets do not die; they are continuing presences; they need only the opportunity to walk among us in the flesh.”

Woolf is not just concerned with how women procured these opportunities. She was also exploring the nature of creative greatness. For Woolf, “it is fatal for anyone who writes to think of their sex. It is fatal to be a man or woman pure and simple; one must be woman-manly or man-womanly.” What was needed was what the poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge called the “androgynous mind.” Woolf believed that Shakespeare (and his sister) possessed such a mind, which she suspects is “resonant and porous; that it transmits emotion without impediment; that it is naturally creative, incandescent and undivided.”

Lori L. Staleri on Flickr

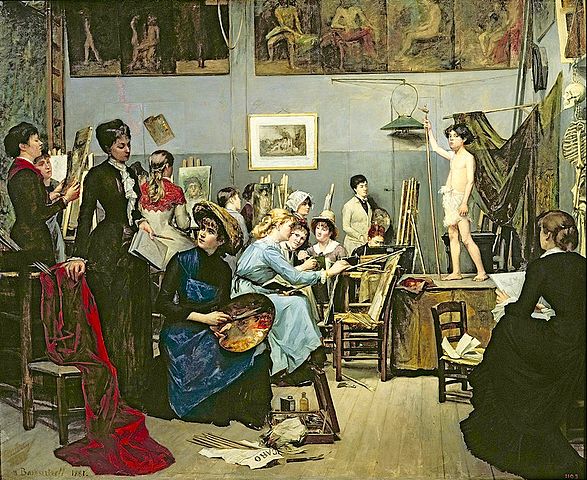

Fast-forward 42 years to 1970, when a New York art dealer expressed regret to newly minted Vassar philosophy graduate Linda Nochlin that he couldn’t find any good women artists to show in his gallery. “Why have there been no great women artists?” he asked, implying that this lack of talent was a natural and ongoing condition. One year later, Nochlin published her seminal rebuttal in ARTnews magazine, defiantly echoing the rankling question in her title. The much-discussed polemic kick-started feminist art history. Among Nochlin’s trenchant observations was her assertion that “the fact of the matter is that there have been no supremely great women artists, as far as we know, although there have been many interesting and very good ones who remain insufficiently investigated or appreciated; nor have there been any great Lithuanian jazz pianists, nor Eskimo tennis players, no matter how much we might wish there had been.” Historically denied access to art education and nude models (at a time when figural work reigned supreme), and lacking materials, peer support, exhibition opportunities and patronage, only a few female painters managed to produce estimable works.

Although her concerns are different from Woolf’s, Nochlin also wants not only to correct the lack of opportunity but also to reframe received ideas about creative greatness. She vigorously challenges what she believes is an outmoded notion of “greatness” by redefining what success looks like in our time and describing the new kinds of art that women have actually been making. She argues that “much of the most interesting feminist art is being created by women from non-western settings. This has nothing to do with primitivism or nature, but rather with specific situations: women artists in Asia, Africa, and Latin America and Australia, in touch with contemporary media, sophisticated theory, and international art production, are creating new kinds of visual languages to embody new meanings, new interpretations of the situation of women in different cultures – complex, acerbic, vivid, contrarian and often, dare I use the word? Beautiful.” Many of these artists are identified in Nochlin’s follow-up essay, “‘Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?’ Thirty Years After.”

Intrigued? If so, join me this summer at Toronto Pursuits. Make Room for Women Artists is a week of morning seminars and slide shows devoted to the foundational questions posed by Woolf and Nochlin. What is genius? What is greatness? Should the creative mind be androgynous? The timing seems exactly right for a close and engaged consideration of the contributions and net gains of women artists and writers in the 20th and 21st centuries. Let’s not let their achievements go unobserved.

– Betty Ann