THE PLACE

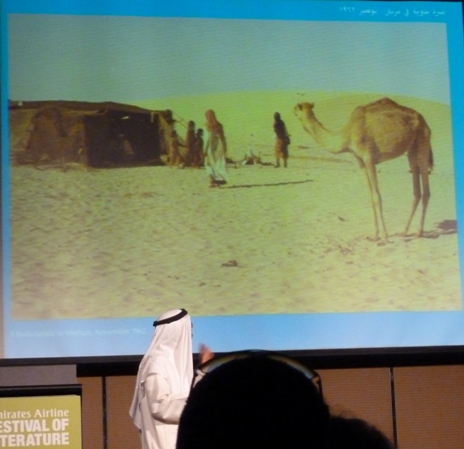

In just a few short decades Dubai has been transformed from a sleepy trading village into a regional powerhouse for commerce and finance — and it has the skyscraper-filled skyline to show for it. It boasts the world’s tallest building, the Burj Khalifa, which handily surpassed the CN Tower when it opened in 2010 (828 metres to 555 metres).

In just a few short decades Dubai has been transformed from a sleepy trading village into a regional powerhouse for commerce and finance — and it has the skyscraper-filled skyline to show for it. It boasts the world’s tallest building, the Burj Khalifa, which handily surpassed the CN Tower when it opened in 2010 (828 metres to 555 metres).

After the shock of the sheer unlikely physicality of Dubai, my second impression had to do with how the place is run. We were told a kind and benevolent king (aka a sheikh) looks after all his subjects. In exchange, his subjects do not criticize the government or offend the national social and religious values.

Here, to give a bit of perspective on this fairy tale kingdom, is a bit of newly acquired history of Dubai and the six other desert kingdoms that make up the United Arab Emirates. The UAE is a very young country, a federation of seven emirates on the south shore of the Persian Gulf established in 1971. One of its founding principles is that the government provides to its citizens free education, healthcare, housing, and employment.

Dubai is the glitzy sister of neighbouring Abu Dhabi, the country’s capital. Each has a population of about 2 million. The total population of the UAE is about 9 million. You’ve probably not heard of the other five Emirates. The country is ruled by six royal families. These ruling families were originally selected by their tribes, a practice that dates back more than 150 years.

While the Gulf states are not democracies, neither are they despotic or repressive regimes. Instead, they are “benevolent and paternalistic.” The government is said to get its legitimacy from tribal roots.

A local may speak for most citizens when he says, “Tribal politics, where people highly respect the elders, the sheikh, is still there. Deep inside of us we still are pretty much as tribal as you would expect us to be. . . . There have been no revolts.” Governments in Tunisia and Egypt have fallen. But in the United Arab Emirates, wealth and tradition are blunting any thoughts of rebellion. The logic of the governing system is quite simple: why enact political reform when the old social contract is still binding and almost all of life’s necessities are amply provided for? No one is genuinely interested in changing the political status quo when prosperity, security, and stability are fully guaranteed.

I was surprised to learn that the Emirati citizens represent only 10 percent of the population of Dubai. The others come from all over the world, with very large numbers from South Asia. About 240,000 British citizens and about 40,000 Americans live in Dubai. Many expats have made a permanent move, while others come for several years. About 70 percent of the population are men, the source, I would think of serious social problems.

I was surprised to learn that the Emirati citizens represent only 10 percent of the population of Dubai. The others come from all over the world, with very large numbers from South Asia. About 240,000 British citizens and about 40,000 Americans live in Dubai. Many expats have made a permanent move, while others come for several years. About 70 percent of the population are men, the source, I would think of serious social problems.

All these foreigners do not enjoy the perks of citizens, but a combination of carrot (no income or sales tax and generally high incomes) and stick (the threat of arrest or deportation) have created a quiescence not found in most parts of the world. The business-friendly attitude that characterizes residents throughout the Emirates is reflected in their attitude toward government, where pragmatism triumphs over democratic longings.

In general, Dubai prides itself on being more open and tolerant of difference than other countries in the region, and many accommodations are made to permit divergent lifestyles as long as they are out of sight. For instance, rowdy bars can be found at the top of many skyscrapers, while the street-level restaurants and cafés remain dry and family-oriented.

In general, Dubai prides itself on being more open and tolerant of difference than other countries in the region, and many accommodations are made to permit divergent lifestyles as long as they are out of sight. For instance, rowdy bars can be found at the top of many skyscrapers, while the street-level restaurants and cafés remain dry and family-oriented.

FUTURE OF CULTURE

When it comes to the arts in Dubai, there is a palpable and cosmopolitan buzz. It is not just literature. The Art Dubai week was just starting as I left. The week before was the Dubai Food Festival. As the royal city state aspires to be the biggest and best in every possible endeavour, my takeaway question is about the sustainability of the momentum given the limits on freedom of expression, which may be largely self-imposed, as they were at the literary festival in 2009.

As my trip went on, I didn’t detect any undercurrent of dissatisfaction.

Our guide was a hip young man from Romania. He said that the limits on free expression under Communism were far more stringent than in Dubai. (He also said that after the fall of Communism, life worsened greatly with severe food shortages.) For Gabriel, Dubai is a paradise. He cannot wait for the opening of the new opera house. Dubai was also a bit of heaven on earth for the vibrant and talented pair of Muslim sisters from South India who founded a highly successful (and hugely fun) Frying Pan Food and Culture Tours. Their parents chose to bring the family to Dubai for a better quality of life. They were prepared to exchange the vote (and what they described as crime, corruption, and chaos) for safety, security, efficiency, cleanliness, and trust in government.

These and other eager young people running art galleries and theatres are full ideas and plans. An opera house to rival Sydney’s is in the works. The world’s first eco-friendly mosque is about to open.

Dubai clearly has the money to underwrite grandiose capital investment in its cultural aspirations. But the arts, it seems to me, are by their nature about inquiring, questioning, and rocking the status quo.

While respect for tradition and civility, and civil discourse are to be lauded, I think it inevitable that there will be increasing pressure from both within and without for a broadening of public debate in the arts, in the press, and in the public square. It’s awkward to be the best when it comes to human development indexes yet down the totem pole when it comes to freedom of expression to speak truths as individuals perceive them.

Dubai clearly has the money to underwrite grandiose capital investment in its cultural aspirations. But the arts, it seems to me, are by their nature about inquiring, questioning, and rocking the status quo.

While respect for tradition and civility are to be lauded, I think it inevitable that there will be increasing pressure from both within and without for a broadening of public debate in the arts, in the press, and in the public square. I think the young people will not allow Dubai to become a shiny cultural assembly line.

I will watch with curiosity and care to see if there is a workable local resolution to this tension. I would very much like to offer a Classical Pursuits trip to Dubai to explore its cultural aspirations and constraints. Please let me know if you are interested. And please share your own experiences in this part of the world. My trip was short, and I still have much to learn about this fascinating place.

An afterthought

As always, this trip also got me looking inward, this time more critically at our own Western democracies. The youthful optimism I could feel everywhere we went was a refreshing change from a weary cynicism that I detect at home. The wind in our sails during the ’60s does not to blow as strongly among the Millennial generation. Somehow it is a little harder to wave the flag for the wonders of democracy, freedom of expression, open-market economies, meritocracy, the rule of law, and other underpinnings of the West. How far have we strayed from our espoused collective goals of “peace, order, and good government” (Canada) or “one nation, indivisible, with liberty and justice for all” (U.S.)?

More colourful images await in my Dubai slideshow.