[Editor’s note: We at Classical Pursuits are excited to welcome back John Riley to Toronto in July 2018. In 2017, John led a seminar on the nature of knowledge. His upcoming seminar, Listening to the Voices of Resistance, has its roots in John’s experience of growing up in the American South but reaches across cultures and civilizations to ask always-urgent questions about power, oppression and justice.]

What do you do when your opposition does not reveal itself to you in any obvious way? When your oppressor fails to pick a fight with you out in the open? When he often changes shape or quickly melts away, insisting that you are the one with the problem? How do you fight against that? Can you? Should you even try?

by Christiaan Tonnis

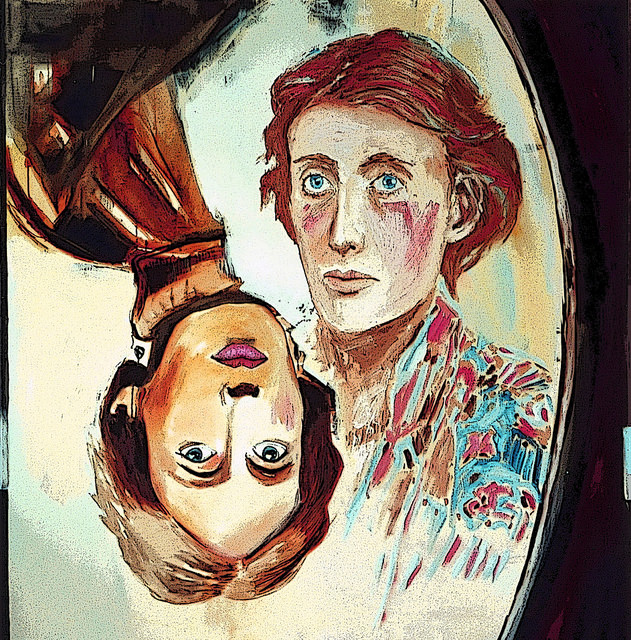

Virginia Woolf in “A Room of One’s Own” and Claudia Rankine in Citizen recognize the complexity of living under social norms that are humiliating and insidious. Both women express frustration with their status, and both identify devastating consequences that come from it. Unlike the other authors we will read in our seminar, however, neither Woolf nor Rankine establishes a clear goal for her resistance or sharply defines her adversary. They sound a very solitary note in their struggles. As such, their examinations of oppressed and oppressor are psychological in content as well as in form .

Still, there is wit and anger in both women’s observations that display a clear element of protest. Something is wrong in the world’s perception of women and African Americans, and it needs to be fixed. In “A Room of One’s Own,” Woolf visits the British Museum and determines from a review of books there that woman, although “the most discussed animal in the universe,” is depicted by male writers in laughably inconsistent ways. Women are regarded as both morally inferior and morally superior, both more intellectually astute and far less intelligent than men. Woolf wonders aloud why men can’t draw any consistent conclusions. She does have choice words for misogynists, arguing that it is their fear of inferiority that drives their hatred of women.

“Women have served all these centuries as looking glasses possessing the magic and delicious power of reflecting the figure of man at twice its natural size.”

–Virginia Woolf

Paradoxically, Woolf sees some advantage in the mystery men make of women. She thinks men are driven by women to build empires and fight wars. She goes so far as to attribute the advance of the civilized world to the male’s drive for female approval, although readers can argue about the level of sincerity in her claim. If it weren’t for women cheering men on, “we should still be scratching the outlines of deer on the remains of mutton bones and bartering flints for sheepskins…”

Rankine’s prose poem Citizen uses the African-American tennis superstar Serena Williams to expose society’s flawed and damaging perceptions about race and gender. Williams has an obscene outburst following a referee’s highly suspect call at a critical time in a match. Instead of characterizing her temper as inappropriate but somewhat justifiable, the white television broadcasters consider her demonstration to be “insane.” Williams’ punishment is extreme: loss of the match, an $82,500 fine and two years’ probation meted out by the Grand Slam Committee.

“You take in things you don’t want all the time…Then the voice in your head silently tells you to take your foot off your throat because just getting along shouldn’t be an ambition.”

–Claudia Rankine

In contrast to Woolf, Rankine sees no hidden advantage in Williams’ circumstance: “…if Serena lost context by abandoning all rules of civility, it could be because her body, trapped in disbelief—code for being black in America—is being governed not by the tennis match she is participating in but by a collapsed relationship that had promised to play by the rules.” And when a black woman reacts to the violation of the rules, instead of looking at the ruling body’s violation, all attention is trained upon the reaction of the minority, who is behaving in an “insane, crass, crazy” way.

“A collapsed relationship” could be the phrase that both Woolf and Rankine might use to describe the intersection of women or people of color and society today. It was never a safe relationship for them in the past, but the rules were more clearly drawn and subjugation was the norm. Now, with the clear injustices of Jim Crow segregation or explicit prohibitions against women to vote or work absent, the dangers are less visible, complicating the work of protest. The old, unjust norms have collapsed now, gone in the minds of the privileged majority but still present to the oppressed. How must the voices of resistance adapt to still be heard? Do Woolf and Rankine provide workable models?

I hope you will join me and other Toronto Pursuits participants in Listening to the Voices of Resistance for a week of discussion on philosophical and practical questions that affect us all.

– John