[Editor’s note: Musician, writer, and broadcaster Rick Phillips returns to Toronto Pursuits with A Symphonic Symposium. What does the symphony mean to you? Reflect on this and other questions as you learn about the history of this musical form and listen to and discuss symphonies from across the centuries.]

The standard format of a typical modern symphony orchestra concert tends to be an overture or short orchestral work to open, followed by a concerto featuring an international soloist. Then after intermission, the second half of the concert is often taken up with a symphony by one of the great composers. It’s a format that continues to work well, building through the evening, with the “meat-and-potatoes” – the symphony – as the highlight at the end. But why is the symphony awarded this important status? As a lifetime concert-goer, I think the reason is that the symphony, like other great art forms, reflects the human experience, or life itself. Not only does the symphony offer the full range of human emotion from love, happiness and joy, to anger, sorrow and grief, but it can also reflect the beliefs, values, and aspirations of a certain period, a nation or nationality, or specific historical circumstances. Basically, to borrow from the name of a popular toy store chain, “Symphonies ‘R’ Us.”

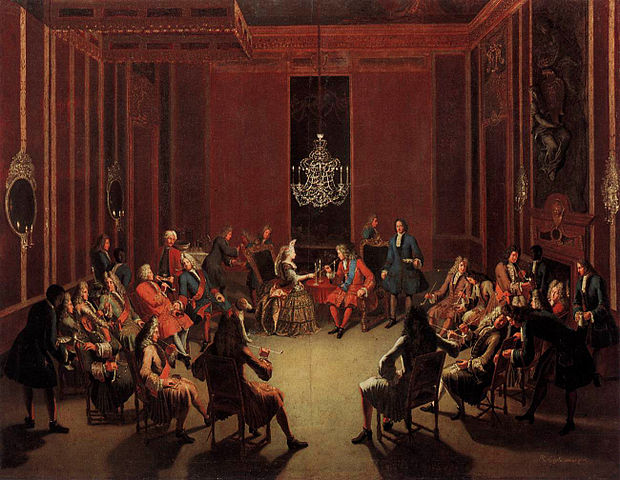

The symphony evolved in the early 18th century out of earlier forms, including the Italian opera overture, the baroque concerto grosso, and the baroque suite. At the time, it was largely a form of entertainment for the upper classes, who often maintained orchestras at court as a status symbol. For example, the court in Mannheim along the Rhine River in Germany was very aware of the aristocratic status a crack orchestra could supply to any court. The on-site orchestra in Mannheim was so good that it was known across Europe as “an army of generals.”

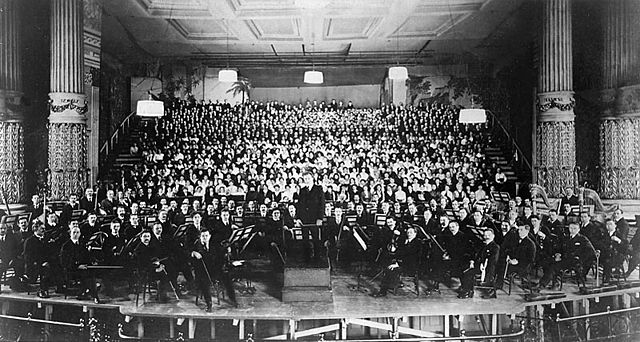

By the second half of the 18th century, Franz Josef Haydn, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, and others standardized the symphony into three or four movements with a variety of forms, speeds, styles, expressions, and emotions. It grew in size, adding new instruments as they were developed, but it also grew in conception and scope, becoming, in effect, “a sonata for orchestra.” But after the French Revolution in 1789 and the sweeping social, political, and cultural changes that resulted in Europe, the symphony evolved to the point where it was capturing those changes in music. Now, with the rise of a middle class in the 19th century, the symphony began to represent a broader slice of humanity and their reality, their hopes and dreams. This continued into the 20th century, where composers often employed the symphony to capture the events and resulting feelings of the day, whether it be war, peace, devastation, or triumph.

In my mind, a study of the development of the symphony is really a study of history from the start of the 18th century to the present day. From aristocracy to democracy to socialism, communism and dictatorships, the broad range and scope of the symphony are nicely drawn by a true story of the meeting of two great composers, both of which we will look into in my seminar at Toronto Pursuits 2017.

In 1907, two great symphonic composers met and traded ideas and opinions about the symphony. The Finnish master Jean Sibelius remarked to the Austro-German Gustav Mahler that what he enjoyed most about the symphony was its logical structure and architecture, like nature. You can detect this trait in the Sibelius symphonies by how he often transforms small, simple building blocks of sound into a complex whole. But Mahler disagreed, replying, “No—a symphony must be like the world. It must embrace everything!” Mahler’s symphonies are philosophical essays that wrestle with the reasons for our existence, and life, death, and life-after-death.

I like to think that both Sibelius and Mahler were right. The symphony can be many things to many people, but in the end, it tells us about ourselves. I hope you’ll join me and the participants of A Symphonic Symposium: Sources, Symptoms and Solutions for a fascinating and stimulating journey through the history and evolution of the symphony.

– Rick

Image credits: Featured image, Conductor Matthias Manasi and the Kazakh State Symphony Orchestra by ParcodellaMusica at Wikimedia Commons; Tabakskollegium of Frederick I at Wikimedia Commons; Napoleon Crossing the Alps by Jean-Louis David; Wikimedia Commons; Philadelphia Orchestra at Wikimedia Commons