It’s not often that you get to stand on top of $2 billion.

That’s the approximate value of the millions of Champagne bottles storied under the Avenue de Champagne, in the town of Épernay.

And it’s not everywhere that you get to see 70 million years of history displayed before you. Millions of years ago, northeastern France was an ocean. As the ocean waters receded, what was left was the thick former seabed of limestone and sandstone. Millennia later, people would realize this mix was excellent for growing grapes and, deeper down, storing bottles of Champagne at constant temperature and humidity in the more than 60 miles of chalk cellars that would eventually be dug.

Above and below ground, the elegant Avenue de Champagne is a feast for the mind and the senses, and one of the places I’m excited to visit with you on our upcoming tour Art and Resistance in WWII Paris and Champagne. Take a stroll with me down this famous street:

Before there was Champagne, there were the Romans. Their road system connected modern-day nearby Reims with Strasbourg and points farther east. Épernay was a marshy, brambly area that was the site of a Gallo-Roman settlement that most sources say dates to the early 5th century CE.

As political fortunes—and with them the map of France—changed, Épernay as we know it began to take shape. Historians know there were large land holdings outside the city walls, in the area where the Avenue de Champagne now is. In 1145, a wealthy citizen built a hospital in this area, and the road that led to it was called “chemin de l’Hôpital.” It later became “rue de la Folie.”

The 17th century brought big developments. In 1744 the road was part of the newly completed route royale (royal road) no. 4, connecting Paris and Germany. (Louis XVI would later use this road to flee Paris during the Revolution.) About a decade later the city gate that separated Épernay from the road was torn down, and in 1793 the road was paved with sandstone.

According to Véronique Foureur, the historian at Moët & Chandon, this was also the year that Jean-Rémy Moët established his Champagne house along the road, in part to take advantage of being on this major trade route. In 1720, his grandfather had dug a small cave (cellar) here, possibly the first to do so in Épernay as he sought to perfect the méthode champenoise of in-bottle fermentation. City records note in 1805 that Champagne houses had recognized the superiority of the cellars dug along what was now Avenue du Commerce, and were quickly expanding here.

Throughout the 1800s more headquarters, offices and reception houses sprang up, along with private houses of Champagne producers and merchants. There was the Château Perrier, today a museum; the Château de Pékin (Beijing) named after Napoléon’s entry into the Chinese capital; and the art nouveau inspired Perrier-Jouët. Producer Eugène Mercier dug his caves in such a way to connect them directly to the railway that had arrived in 1849, linking Paris and Strasbourg.

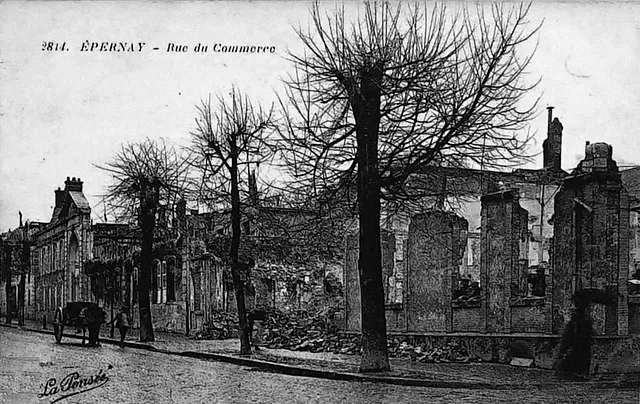

Cellars were raided in the Franco-Prussian war and the early part of WWI, with thousands of bottles of Champagne taken by the German army. And in July 1918, most of the buildings lining the Avenue du Commerce were destroyed by shells and bombs. As happened throughout France, Épernay and the Champagne industry were rebuilt after the war, and in 1925 the municipal council renamed the road Avenue de Champagne.

During WWII, the Nazis commandeered the cellars again to meet their insatiable demand for Champagne. According to Foureur, the Moët & Chandon house sealed off some of the older parts of their cellars, protecting bottles from theft. The region became an important part of the Resistance: Records for Nazi Champagne orders and deliveries provided intelligence, and the caves provided protection for Resistance cells and citizens. Some Champagne producers served as invaluable Resistance liaisons. The fascinating history of Champagne during WWII is a major part of our upcoming Art and Resistance tour.

Today, as in the 19th century, there is a dizzying array of architectural styles from renaissance to art nouveau represented in huge houses like Moët and in smaller ones owned by producers you may have yet to discover. Admiring them is one of the joys of walking along the current Avenue de Champagne, lively with travellers and students from the historic lycée (high school) Stéphane-Hessel.

My visit to the avenue was also an opportunity to fulfill a promise I’d made to a dear friend. Classical Pursuits traveller Dawne Bernhardt and I hit it off right away when we met more than 10 years ago. Dynamic, up-for-anything Dawne was my soulmate in grandmother form. She worked and travelled all over the world, making friends wherever she went. Dawne had impeccable taste in everything, including Champagne, and as a wedding gift she had offered my husband and me a bottle of Perrier-Jouët with four delicate flutes bearing the maker’s signature flower design. Before she died last year, I promised her that someday I would visit the Champagne house. At the lovely, flower-filled bar, I raised a glass to her extraordinary life and the many adventures we had together.

What will you toast in Champagne? Join me and our very special host, author Bryn Turnbull, for Art and Resistance in WWII Paris and Champagne for what will be an only-at-Classical-Pursuits experience.

Sources: “À Epernay, l’Avenue de Champagne cache 200 millions de bouteilles!” (La revue du vin de France); “Hidden Under This Street in France Is a Fascinating History—and Champagne Worth Billions” (AFAR); “Champagne and its history” (Comité Champagne); “Champagne Hillsides, Houses and Cellars” (ICOMOS/UNESCO); “Épernay” and “Avenue de Champagne” (Wikipedia); “The Roman Roads of Gaul Visualized as a Modern Subway Map” (OpenCulture)