“In Cold Blood? Why did you decide to do that?” This has been a common reaction among friends and acquaintances when they learn I plan to lead a shared inquiry into Truman Capote’s work this summer at Toronto Pursuits. Even those who knew my longstanding interest and in-depth study of writers such as Fitzgerald, Hemingway, James, Bellow, Malamud, and Roth (Henry and Philip) seemed surprised.

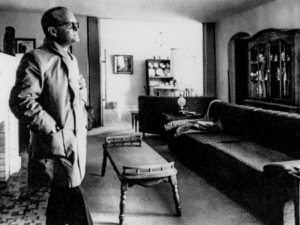

Although Capote may have been on my Ph.D. reading list of writers who defined the 1960s, including John Updike, Thomas Pynchon, Joseph Heller, Ken Kesey, Kurt Vonnegut, Norman Mailer, and Harper Lee, among others, I must confess that he fell off my radar screen decades ago. His work briefly popped back into my consciousness when I saw the 2005 biopic, Capote, with a terrific performance by Philip Seymour Hoffman. And of course, I would be reminded of him when I would view (time and again) Audrey Hepburn in her iconic role as Holly Golightly in Breakfast at Tiffany’s.

Then, last year, I saw the FX series Feud: Capote vs. The Swans and my long-forgotten interest in Capote’s extraordinary, surprising and sudden rise to literary prominence was again piqued.

A fascination with stories of horrific criminals such as the notorious murderers Jack the Ripper, the Lindbergh baby kidnapper, or Leopold and Loeb is not new. As mass media developed and literacy rates rose in 16th-century London, for example, crime pamphlets full of the details of capital crimes circulated widely. Trial accounts were published alongside less obviously factual works like ballads.

As media formats and access have proliferated, “straight” newspaper reporting (itself of varying accuracy) of well-known crimes exists alongside stories told in exaggerated and embellished ways that in some cases mythologized and romanticized the perpetrators. For example, as the Depression caused severe hardship across American, many considered bank robbers Bonnie and Clyde to be Robin Hood figures. Guerilla fighter and bank robber Jesse James was seen as a “symbol of Confederate defiance against Reconstruction policy.” Even today, someone like Luigi Mangione, who is accused of fatally shooting of UnitedHealthcare CEO Brian Thompson, has taken on mythic fascination for hundreds of people who have no real knowledge of him beyond the media reporting and social medial reactions.

Unlike other murderers who sometimes achieve mythic status, the killers in Capote’s novel were not seen as larger-than-life folk heroes committing murder to draw attention to a higher moral or ethical issue. The Clutter family murders may have gone unnoticed beyond the local Kansas media; it was not a national story. The human tragedy of bloodshed and murder related to robbery occurs all too often in modern America. But Capote’s telling of it engages readers at a different level.

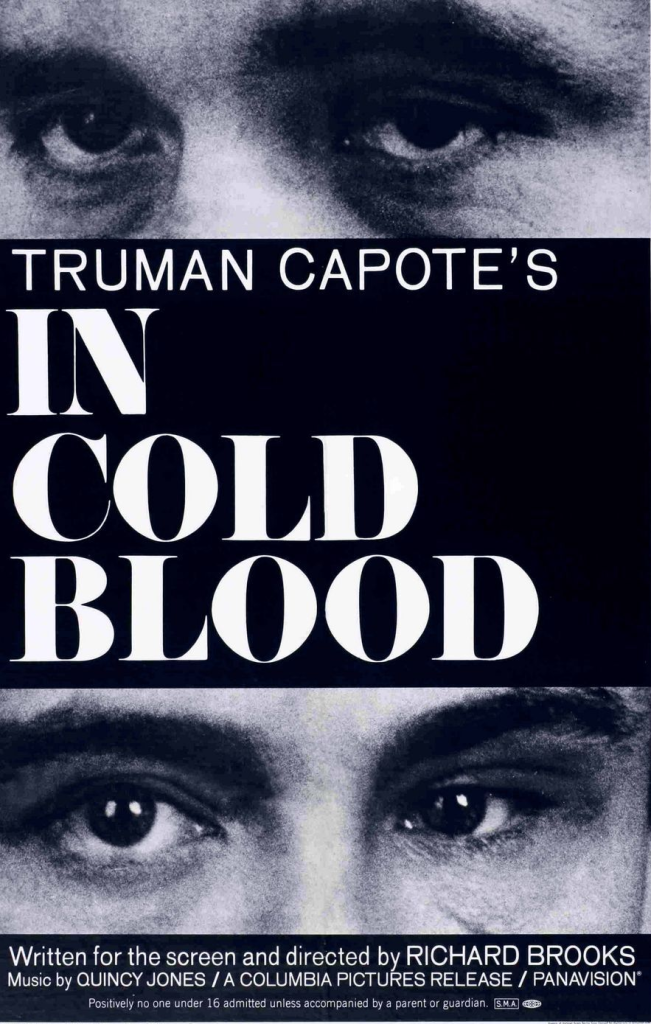

First excerpted in four parts in 1965 in the New Yorker, the installment series of “In Cold Blood” was a sensation. The publication in full book form the following year ensured Capote’s place in the contemporary literary canon. The book became an immediate bestseller and stayed on the New York Times bestseller list for nearly four years.

Why? What makes this work resonate so strongly?

For readers in the 1960s, part of the answer may lie in the idea that In Cold Blood represents a totally new literary art form, what Capote termed, the “nonfiction novel.” Its importance, I came to realize, is not to be underestimated. Yes; the story and the events depicted actually happened. That’s the nonfiction. Capote, in a famous 1966 interview with George Plimpton in the New York Times, declared that his choice of material in choosing to write a true account of “an actual murder case—was altogether literary.” For Capote, the nonfiction novel was a “serious new art form.”

But what makes this book good (or perhaps even “great”) literature? Is it closer to a novel than to detailed journalistic reportage? As readers of American fiction, we have admired Faulkner’s technique in The Sound and the Fury where one narrator tells a version of events as a counterpoint to a previous speaker. Capote uses the same technique to get at the “truth” of the events. For Capote, the place where factual journalism ends and imaginative literary fiction begins may sometimes be unclear.

This undefined place may connect to what draws us to true crime. Legal scholar Patricia Bryan points out that we have a strong desire to understand what motivates other people, especially when their actions are extreme and defy explanation. We seek meaning when there doesn’t seem to be any. Bryan also notes that we like to be scared, from a safe distance: “It speaks to why people go into haunted houses or ride a roller coaster. There’s something about facing danger when it’s not real, it’s not personal. People […] like to see the dark recesses of someone’s mind,” she says.

Criminologist Brian Levin suggests criminals can become symbols of or explanations for things we don’t understand: “[Mason’s] violence struck at a fixtures of American society that people weren’t necessarily familiar with. It was counterculture gone awry, race war, violence as a means of political expression but not targeting traditional symbols (such as a president) which then fed into this whole concept of society spinning out of control.”

Is our desire to understand and find meaning even stronger when a crime does not seem to be motivated by any purpose? Even as we condemn a murder committed in the name of love, jealousy, hatred, or out of desire for money or to protect one’s reputation, we can recognize the emotions motivating the act. But the acts of Dick Hickock and Perry Smith to the Clutter family seem utterly meaningless—and that can be hard to sit with, as common as it might be in our world.

Do Capote’s detailed, in-depth psychological and sociological portraits of Hickock and Smith address some of these urges in a deeper, more meaningful way than easy sensationalism? Does it help us deal with the randomness of the world we live in?

In our seminar this July we will assess the literary worthiness of this new genre and what it offers. In evaluating Capote’s exploration of Smith’s and Hickock’s backgrounds, we will explore through our own shared inquiry themes of class, materialism, nature vs. nurture, the artistic sensibility and sexuality and in some ways, like Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby, the shattering of the American dream.

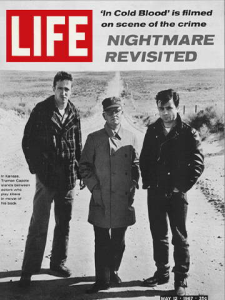

Given the extraordinary popularity of Capote’s novel, it was not surprising that Hollywood sought to adapt the novel to film. Director Richard Brooks quickly purchased the rights from Capote after reading a draft of the novel to make his 1967 movie. Capote expressed his approval of Brooks’ adaptation. Like the novel did, Brooks employed a documentary-like style where simultaneous events are witnessed from differing perspectives. The four-part structure of the novel, with “scene” breaks, is a natural and seamless transition to a film version.

But how well does the film work? While both versions appeal to the ever-growing popular obsession with true crime, Brooks’ changes to “adapt” a book of approximately 350 pages to a 134-minute movie are worthy of our discussion. Interestingly, another very popular Truman Capote book, Breakfast at Tiffany’s also became a big Hollywood release; this film was “based” on the book and is, in many ways, director Blake Edwards’ reimagining of Capote’s original vision. Ironically, the beloved film version of Breakfast at Tiffany’s popularity has far exceeded the novella on which it is based.

Why are some books that are turned into films and which attempt to be closely adapted to the original successful and others less so? Is such transformation among genres worthy of consideration? Relatedly, why are some films more critically acclaimed when they are simply inspired by the literary original?

I look forward to the prospect of our shared in-person investigation at Toronto Pursuits as we discuss In Cold Blood, its movie version, the merits of a new literary genre, and our complex relationship to true crime.

— Herb

Sources:

“The Bloody History of the True Crime Genre.” JSTOR Daily, https://daily.jstor.org/bloody-history-of-true-crime-genre/. Accessed 4 Mar. 2025.

“The History of True Crime.” The New York Times, 1 Feb. 2024, https://www.nytimes.com/2024/02/01/books/review/true-crime-history-murder.html. Accessed 4 Mar. 2025.

“Bonnie and Clyde: American Criminals.” Encyclopædia Britannica, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Bonnie-and-Clyde-American-criminals. Accessed 4 Mar. 2025.

“Why Are We Fascinated by True Crime?” University of North Carolina, https://www.unc.edu/posts/2024/01/11/why-are-we-fascinated-by-true-crime/. Accessed 4 Mar. 2025.

“Why People Are Still Obsessed with the Manson Murders.” Vice, https://www.vice.com/en/article/why-people-are-still-obsessed-with-the-manson-murders/. Accessed 4 Mar. 2025.

Th