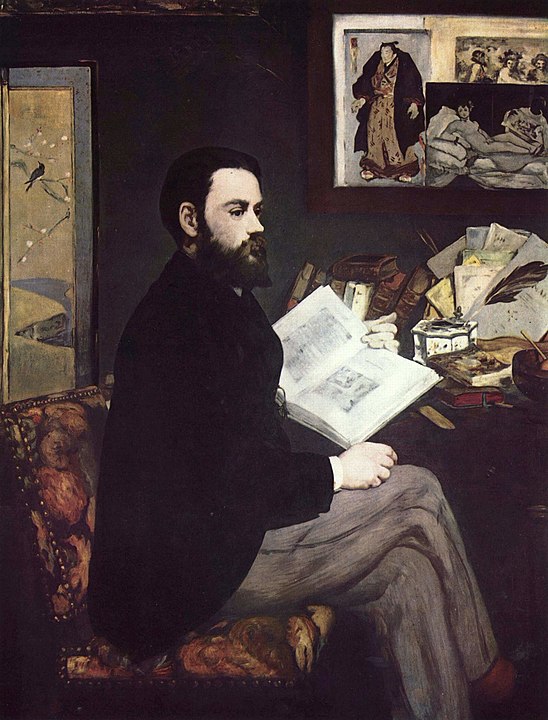

He’s been described as the most famous author of his day, as “literature’s greatest whistleblower.” His influence on French, American, and world literature is undisputedly huge. And his books, as the title of this post suggests, are full of three things people love to read about, even if they don’t always admit it.

So why did I avoid the novels of Emile Zola for so long?

I first came to Zola in a university class on French literature that threw freshmen into the deep, deep end of the pool. I spent many all-nighters with my classmate Theresa, who lived across the hall, working our way with painstaking slowness through the novels of Flaubert, Maupassant, and Zola. Our Robert dictionaries in hand, we tried in vain to keep up with each week’s reading.

A class on 19th-century literature at the Université de Montpellier during a semester abroad was equally painful. Never had I worked so hard yet been so hopelessly behind. Today I could not tell you anything about the novels I slogged (partway) through in the early 2000s.

I later built up my ability and stamina for reading in French, starting by reading translations of bestselling crime and detective fiction by Sue Grafton and others before moving on to French detective fiction (polars) and contemporary novels by authors like Patrick Modiano.

But it was a while before I returned to the 19th century and particularly Zola, even in English, and even though I was fascinated by books like Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle and Frank Norris’s McTeague. Sinclair, Norris and others were strongly influenced by Zola’s naturalism and determinism. Zola saw novels as having a scientific purpose, and characters as subjects to test his theories on. He wanted to explore the roles that heredity and environment played on character.

As time passed and I was more and more often immersed in 19th-century French history and culture for Classical Pursuits, it was clear: It was time to read Zola already.

I began with La Bête humaine (The Human Beast or The Beast Within) (1890) and continued with Thérèse Raquin (1867). I’ll be honest — one of my initial impressions was of descriptions of characters’ thoughts and actions that were too repetitive to carry the novels through, repetitiveness that blunted the novels’ impact. Even the scenes of what is clearly meant to be smoking hot sex between Jacques Lantier and Séverine, and Thérèse and Laurent, became more of the same.

A critical reception of Zola’s characters is not new; in the 1960s scholar Richard Grant wrote that “one of the most solidly entrenched verities concerning the novels of Emile Zola is that he cannot create a good character. Despite occasional exceptions […] Zola’s characters cannot compare with those of Balzac [or Dickens, per many critics] as intense living creatures.” The reasons often given for this, says Grant, are Zola’s determinism, his emphasis on the “dehumanizing” role of our animal instincts, and his desire for symbolism that could flatten individual characters’ personalities.

A more careful reading of Thérèse Raquin for a Classical Pursuits seminar revealed deeper complexity even though I still had some of my initial impressions. For example, I found the descriptions of Thérèse’s mother-in-law, paralyzed by a stroke yet still energetically hating Thérèse, to be extraordinary and memorable.

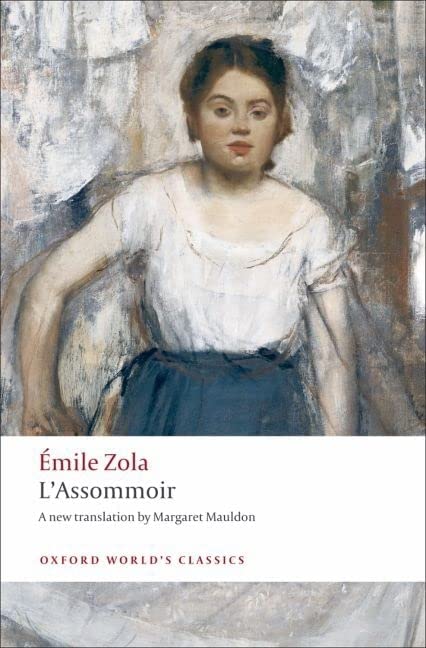

And then I started L’Assommoir (The Drunkard or The Drinking Den), and something clicked. With this book, I am all in. Gervaise, the protagonist, is to me a rich, full character and I am hoping she will prevail although I know she won’t. It’s a novel by Zola, after all.

And then I started L’Assommoir (The Drunkard or The Drinking Den), and something clicked. With this book, I am all in. Gervaise, the protagonist, is to me a rich, full character and I am hoping she will prevail although I know she won’t. It’s a novel by Zola, after all.

In preparation for our May 2023 Paris trip, I’m now deep into the world of the Rougon-Macquart, the family created by Zola for his 20-novel series “The Rougon-Macquart: Natural and Social History of a Family under the Second Empire.” As I relish in the detailed descriptions of street scenes, workshops, coal mines, and homes, I’m still trying to fully understand Zola’s views and his multi-faceted project. Do I agree with his idea of what a novel can or should be? How much of a determinist am I? Zola, in his own writings, said that he meditated at length on every aspect of his characters. In the end, do they come across as “intense living creatures?”

And I’m fascinated by the questions Zola raises. What happens to individuals, and to societies, when the gap between rich and poor is so wide, yet so easy to see across? What will researchers find in the next 10, 20, or 50 years as they look deeper into theories about transgenerational trauma?

I invite you to step into Zola’s world and see what you think. In 2015 the BBC created and aired a serialization of the Rougon-Macquart series, called Blood, Sex and Money; it’s a great place to get started.

Our upcoming seminar with Sean Forester, Paris as Character and The Greater Journey, is a look at the same period from another angle, that of lawyers, doctors, artists, abolitionists, and other Americans of note who came to Paris to make their mark.

And for the pièce de résistance, come to France with me and writers Lisa Pasold and L. John Harris this spring, as we read L’Assommoir and go deep into the belly of 19th-century Paris with Zola and his contemporaries.

— Melanie

Sources: Blood, Sex and Money by Emile Zola. BBC Radio, 2015; Grant, Richard B. “The Problem of Zola’s Character Creation in ‘L’argent.'” Kentucky Foreign Language Quarterly, vol. 8 issue 2. 1961. pp. 58–65