[Editor’s note: Every year Betty Ann Jordan brings colour and style to Toronto Pursuits, and 2019 will be no exception. Join her for Seeing Through Clothes, a seminar that weaves art and history into a larger exploration of what clothes say about us.]

In Seeing Through Clothes, historian Anne Hollander mines fashion in artworks such as these for its rich social content. Making a case for life imitating art, she proposes that “works of art demonstrate not how clothes were made, but rather how they and the bodies in them were supposed to look and believed to look.” In other words, artists have disseminated and popularized not only fashions and styles, but also mannerisms and ideal body types. Hollander takes an erudite but irreverent look at the myriad ideas embedded in representations of the body in Western art, ranging from the philosophical thinking that took 3-D form in well-muscled Greek statues to the elongated figures of 18th-century art before she closes the closet door in the early years of the 20th century. While notions of gender, beauty, and luxury inform clothing, so do spiritual and religious beliefs, textile technologies, and wars. To a lesser extent, Hollander also looks at folkloric and ethnic costumes and clothing in Eastern cultures where artistic representations of the body are traditionally not permitted.

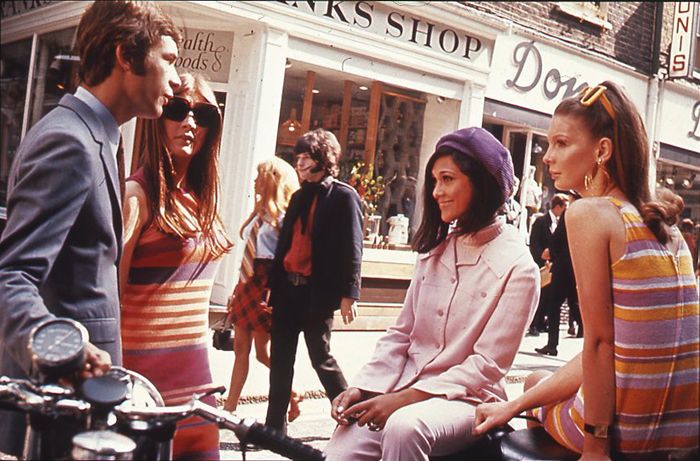

Guided by Hollander, with our discussions enlivened by daily slide shows, we’ll look at examples relating to drapery, nudity, undress, dress, and mirroring as we examine the metaphorical, social, and ideological uses of apparel as portrayed in great works of art.

Picking up where Hollander leaves off, the omnibus text Women in Clothes will be our guide to the eclectic, gender-bending, pop-culture-inflected modes of the past 100 years. An appreciation of the forces at play in recent and contemporary fashion, this book especially lends itself to this year’s theme of community. In Women in Clothes, we learn about the values, relationships, and tensions implicit or explicit in style choices directly from hundreds of women – and one man. Through close reading of selected personal essays and visual art projects, we’ll address such timely questions as: To what extent are communities distinguished through clothing? How does apparel sustain or support social organization, especially among marginalized groups? Can garments be untethered from gender?

What sort of social networks and communication strategies are involved in generating a style or trend? Is there a moral dimension to clothing? How do garments empower? And centrally, are clothing memories the last best emotional link to our mothers and friends?

In considering art à la “mode” (a word that encompasses clothing, accessories, hairstyles, body language and comportment), we’ll see if Anne Hollander’s ideas still stand in the media-saturated, culturally hybrid 21st century. Join me in July for a stimulating week of discovery in Toronto.

– Betty Ann