Upon that night, when fairies light

On Cassilis Downans dance,

Or owre the lays, in splendid blaze,

On sprightly coursers prance;

Or for Colean the route is ta’en,

Beneath the moon’s pale beams;

There, up the cove, to stray and rove,

Among the rocks and streams

To sport that night.

That night of fairies, dancing and bonfires is, of course, Halloween. The holiday’s name comes from an old Scottish term for All Hallows’ Eve, the evening before All Saints Day, the Christian feast dedicated to the memory of the dead, especially saints (hallows).

Many scholars believe Halloween traditions originated from ancient Celtic harvest festivals, such as Samhain (pronounced Sow-an). Samhain marked the end of summer—”the dying of the light and the coming of darkness.” It was a time when the normal order of the universe was upended or suspended. The world of the gods was made visible to mortals on earth, and supernatural forces prevailed.

Similarly, in Mexico, the Día de Muertos festival combines Aztec, Spanish and Catholic traditions. By the time of the Spanish conquest, Aztecs celebrated the goddess of death and the underworld, Mictecacihuatl, with a festival that included dance, blood sacrifice and the presence of marigolds. These flowers were believed to waken the dead with their fragrance. Over time indigenous practices were blended with Christian ones. Like the ancient feast of Samhain, Día de Muertos is a time when the boundaries between the living and the dead fall away, and ghosts or spirits return to earth.

Similarly, in Mexico, the Día de Muertos festival combines Aztec, Spanish and Catholic traditions. By the time of the Spanish conquest, Aztecs celebrated the goddess of death and the underworld, Mictecacihuatl, with a festival that included dance, blood sacrifice and the presence of marigolds. These flowers were believed to waken the dead with their fragrance. Over time indigenous practices were blended with Christian ones. Like the ancient feast of Samhain, Día de Muertos is a time when the boundaries between the living and the dead fall away, and ghosts or spirits return to earth.

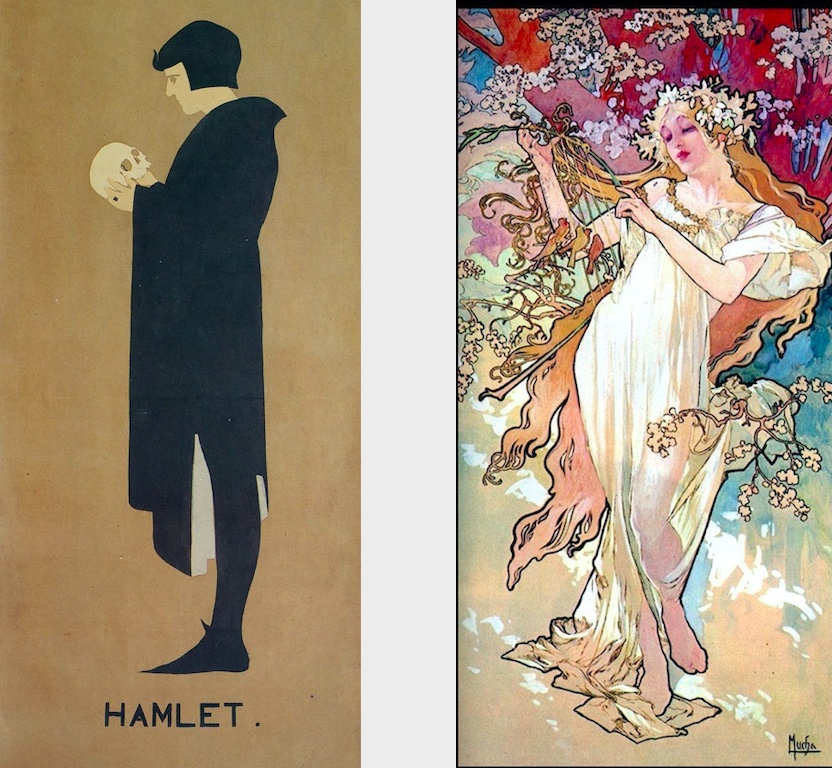

These liminal spaces and the ghosts who populate them have long captured our imaginations and figured in some of our most beloved stories. One of the most famous spirits in literature is the ghost of Hamlet’s father in Hamlet.

Watch the ghost scene in this remarkable film by Grigori Kozintsev (begin at the 21:00 timestamp).

What a contrast between this dark Nordic/Russian Hamlet and a version in both English and Spanish, that Seattle Shakespeare staged earlier this year, or this Mexican adaptation set among coloured lights and Día de Muertos props and figures.

And that’s the beauty of Shakespeare. His plays resonate around the world and offer so many possibilities. I invite you to read them in this spirit in my upcoming Shakespeare seminar. We’ll place special emphasis on themes of truth and illusion in Hamlet. And for a contrast we’ll also connect with light-hearted spirits in A Midsummer Night’s Dream.

And that’s the beauty of Shakespeare. His plays resonate around the world and offer so many possibilities. I invite you to read them in this spirit in my upcoming Shakespeare seminar. We’ll place special emphasis on themes of truth and illusion in Hamlet. And for a contrast we’ll also connect with light-hearted spirits in A Midsummer Night’s Dream.

Much of the joy of Shakespeare is in the magic of live theatre, which we all miss during this pandemic. To relive it for a couple minutes, watch Paul Scofield, one of the all-time greats, in his performance of understated brilliance as the ghost of the elder Hamlet.

But to fully appreciate Shakespeare in the theater, I feel one needs to read and discuss the play first. The experience is so much richer when you understand Shakespeare’s language and the complexity of the characters he creates and the themes he explores. In my shared inquiry seminar, we will unpack the multiple meanings in single lines and find key questions that open the whole work.

For every festival to remember the dead, there is one to celebrate the living. Harvest festivals give thanks for the bounty of the earth, for the apples, grapes, melons, chestnuts, pumpkins . . . the cornucopia!

We will juxtapose the ghost from Hamlet with the buoyant, mischievous spirits from A Midsummer Night’s Dream. In addition to themes of truth and illusion, both plays deal with ideas of love and fertility vs. sickness and destruction. In Hamlet, contagion or sickness is an act of evil, the poison Claudius pours in the ear of the elder Hamlet. His action of course, has tragic consequences. In A Midsummer Night’s Dream, by contrast, the strife between Oberon and Titania temporarily blights the earth, but love and imagination ultimately triumph. The play is full of comic delight. Like Bottom, we feel we are invited to a feast:

“Be kind and courteous to this gentleman.

Feed him with apricots and dewberries,

With purple grapes, green figs and mulberries . . . .

And pluck the wings from painted butterflies

To fan the moonbeams from his sleeping eyes.”

(Act III, Scene I, line 158)

Come join the banquet! This turning point in the year is the perfect time to read these two plays. I look forward to seeing you there.

— Sean

Sources

“Halloween” by Robert Burns

“Samhain,” Joukowsky Institute for Archaeology & the Ancient World, Brown University

“Halloween,” Encyclopedia Britannica

“Samhain,” Encyclopedia Britannica

“Nueve cosas que debes saber sobre la celebración del Día de Muertos en México,” Los Angeles Times

“Day of the Dead: From Aztec goddess worship to modern Mexican celebration,” The Conversation