One of the best things about returning to Paris this spring for the first time since 2019 was experiencing long-anticipated pleasures, both familiar and new. I was happy to once again be swept up in the rush-hour Métro crowds, or sip my favourite aperitif, a Suze, among the lilac trees at a sidewalk café table.

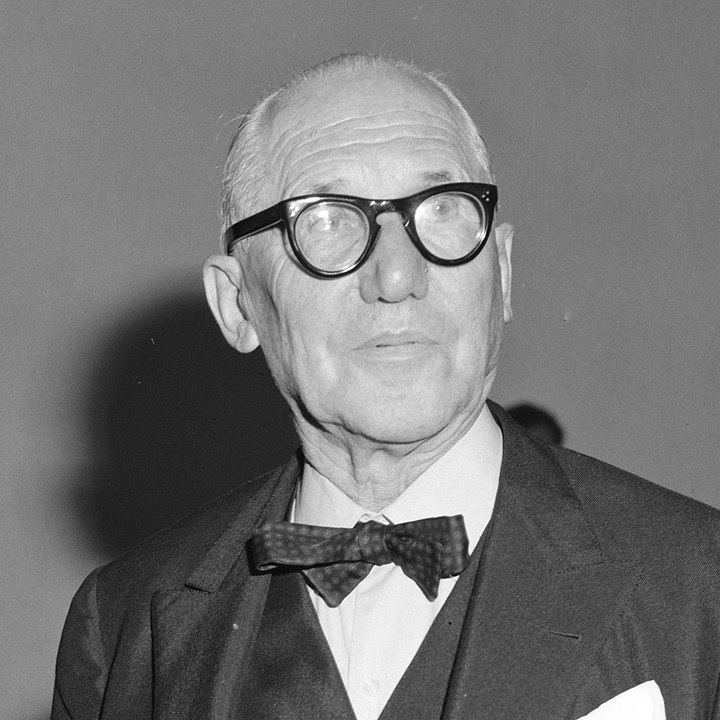

As leader of the April 2022 trip They Came to Paris: Literature 1910 to 1940, I was also eager to share with participants a place new to all of us: the Fondation Le Corbusier. Some of the foundation’s key sites include a group of buildings designed by Charles-Édouard Jeanneret, known as Le Corbusier or Corbu, at the western edge of Paris. They’re far from the blockbuster sites in the city centre and absent from the itineraries of most visitors — even those who come to learn about Paris as a nexus of cultural and artistic innovations during the interwar years.

Those visitors are missing out! The afternoon our group spent learning about the vision and work of Le Corbusier was a highlight of the trip. To reach our first stop, we rounded a corner of Haussmann-style buildings and, as we passed through the foundation’s gate, stepped from the 1860s into the 1920s.

Our destination was the Maison La Roche, commissioned by the banker and modern art collector Raoul La Roche. It stood at the end of a small, private street of modern apartments and houses in a neighbourhood where Le Corbusier and contemporaries such as Robert Mallet-Stevens and Pierre Patout could find space to experiment with their new ideas. This villa, as our art student guide Aurélie explained, was the realization of Le Corbusier’s “five points of a new architecture“: piles or pylons to open up space under a building; a roof garden; a free or open floor plan; horizontal ‘ribbon’ windows; and a free facade. Here they were brought together for the first time. The new building material of reinforced concrete enabled Le Corbusier to make these and other ideas a reality. Interior and exterior walls no longer needed to be load-bearing, so facades could have windows run their whole width and floor plans were no longer determined by the need for load-bearing walls distributed in a certain way.

My favourite room in the villa was the gallery, with ramp (or “architectural promenade”) and built-in light/shade for viewing and protecting La Roche’s collection of paintings by Le Corbusier, Amédée Ozenfant, Juan Gris, Jacques Lipchitz, and Pablo Picasso.

A short Métro ride away was the Le Corbusier Studio-Apartment, where Le Corbusier and his wife Yvonne lived from the 1930s to the late 1950s. (After Yvonne’s death in 1957, Corbu remained until 1965.) The apartment is on the top two floors of an apartment building designed by Le Corbusier that the foundation calls “the first glass apartment building in the history of architecture.” The eight-story building was attractive, and I always enjoy seeing modern architecture among the blocks of Second Empire buildings. But for our eyes used to towers of glass 300, 400, even 500 metres high, the real visual jolt came from climbing the narrow stairs and entering the apartment full of light. It was invigorating to be inside yet surrounded by so much light. Aurélie showed us how colour was used to separate space in the open plan, and line to unite it. We admired the built-in furniture, a new concept at the time, but were not sure how Yvonne Jeanneret would have felt about the open-plan bathroom. (You can see more photos here.)

Although these spaces are nearly 100 years old, they don’t feel it. Standing in them, I still felt the impact of Le Corbusier’s influence and the sense of new possibilities he saw for design, architecture, and the way people interact with their environment. These possibilities played out in complex ways, especially at scale. Le Corbusier’s ideas on urban planning have impassioned defenders and detractors. Visiting the Maison La Roche and the Studio-Apartment made tangible some of the larger ideas we were exploring on our trip: What happens when traditional ways of thinking and being no longer apply to the life you live now? What is the purpose of art? How do you determine what is beautiful? How do you decide what is valuable? These were questions people of the 1920s and 1930s were asking themselves as the changes of the first years of the 20th century were accelerated and made even more dramatic by World War I. There was as little agreement on the answers to these questions then as there is now.

The hours we spent in the world of Le Corbusier that afternoon brought to life what makes Classical Pursuits trips different. By visiting sites that are not exactly hidden but are not always top of mind, we offer even seasoned travellers new experiences. We try as best we can to engage with complex ideas, nuance and contradiction.

We’d love to have you travel with us! Upcoming art and literature trips to European cities include Slant of Light: Dutch and Flemish Old Masters and Thinking Spaces, Drinking Spaces: Paris Café Culture. Each is a focused yet expansive exploration, a way to engage in-depth with the past and the present. To learn more, use the links to download an itinerary or contact us at info@classicalpursuits.com.

A bientôt,

Melanie