“Just look! It’s right there in the painting.” This exhortation from our guide Sara Magister seemed so intuitive, so easy. A painting is there to be looked at. What happens when we take the time to do it?

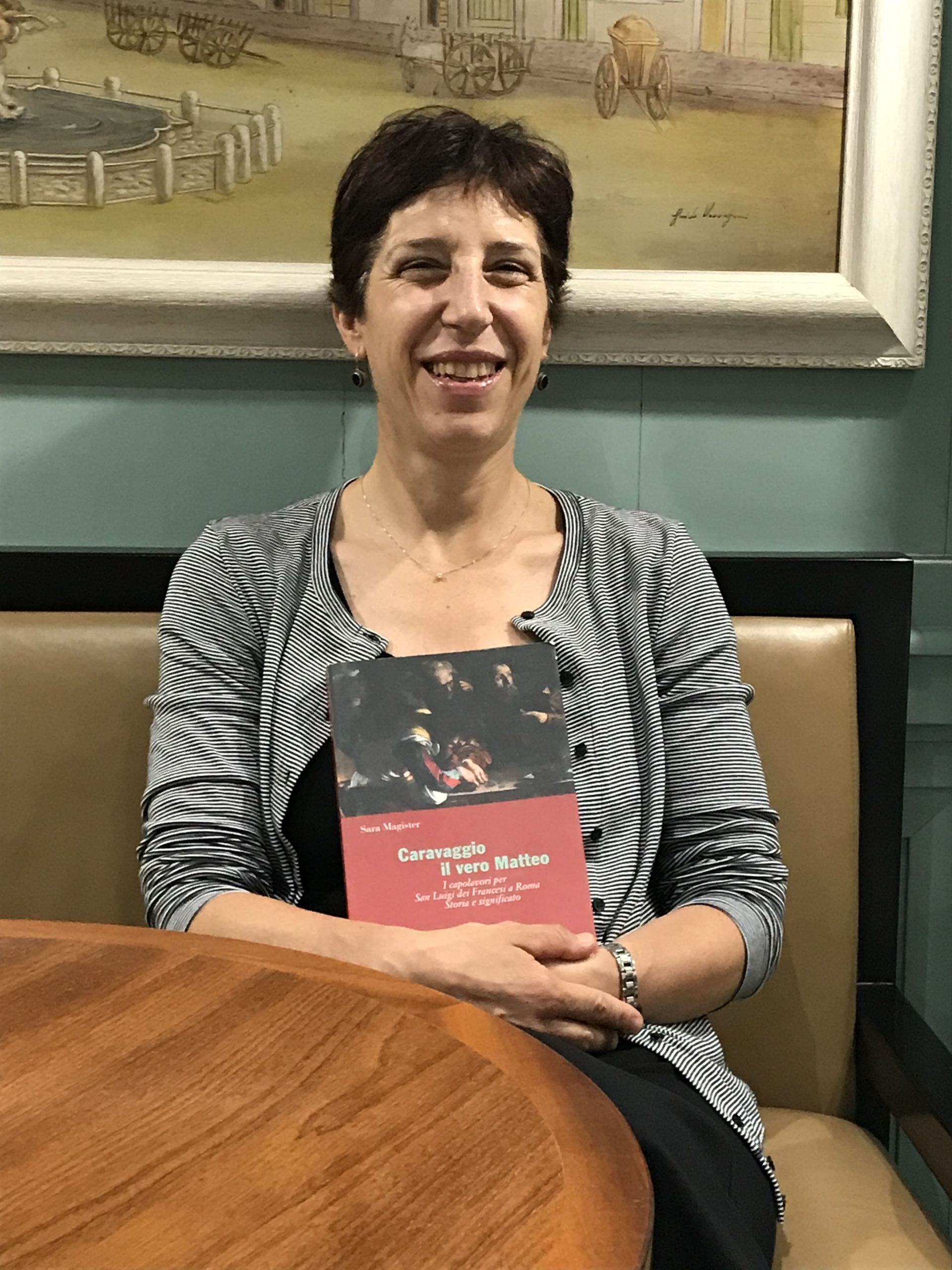

Let me back up a bit. Who is Sara, and which paintings are we looking at? Sara Magister, an art historian, was our guide for the recent Classical Pursuits trip The First Modern Artist: Caravaggio in Rome and Malta. Moving through Caravaggio’s world with her was exhilarating. Sara’s sharing of her vast depth of knowledge about the painter, his technique, and his patrons and contemporaries, was always accompanied by the challenge to look closely and carefully — and, I think, to trust our eyes.

One of the paintings we spent the most time on was The Calling of St. Matthew. Take a look at it. What do you see? Maybe even jot down a few of your impressions before you read on.

Sara would also remind us that it’s critical to see the work as a viewer would. The Calling of St. Matthew is part of a series of three paintings by Caravaggio on the life of the saint; they are hung in the space they were designed for: the Contarelli Chapel of San Luigi dei Francesci (St. Louis of the French), near the Piazza Navona in Rome.

Here is an image I took of the painting:

And another of the arrangement of the paintings in the chapel (Steven Zucker on Flickr):

I know these images cannot fully capture the sense of being at the chapel, but they still offer important information. What else do you see when you look at them?

Sara would point out that because the chapel was private, most 17th-century viewers would, like us, only have the opportunity to see the two side paintings (Matthew’s calling and his martyrdom) from a diagonal viewpoint. But we’re not at a disadvantage because we can’t see them head on. Caravaggio knew how pilgrims to San Luigi would be looking at these paintings from outside the chapel proper and composed them accordingly. Sara would also say there is another light source on the painting you would not see when looking at it in, say, a book: the light from the window above the central painting, which is itself above the altar.

Now that you’ve looked hard, think about how you understand the painting. What is each figure doing? What is the relationship of the figures to each other? To the two light sources? And the big question: Who is St. Matthew?

Following the lead of Giovanni Pietro Bellori, a 17th-century art historian and painter, most historians and critics identify Matthew as the bearded man making the pointing gesture. He’s astonished that Jesus (on the far right) has chosen him, a tax collector and thus someone regarded with contempt by the community at large.

All these critics are literally missing the point, Sara and some other critics argue. Bellori hated Caravaggio, she explained, and in her view misunderstood him at every turn. But knowing that is not necessary to understanding this painting. Take another look at the bearded man’s hand. He’s not pointing to himself, as the dominant interpretation says. His hand just isn’t turned that way. He’s pointing to the young man who’s seated at the far left of the table, looking down at the money. That’s Matthew. “Him?” the bearded man is asking in disbelief at Jesus’s choice.

The young Matthew is caught in a critical moment, Sara explained. For the painting is not about the conversion of St. Matthew, but about his calling. He might not have even fully realized what is happening, but he senses something important is up. This is revealed to us through the tension in his body. His bent right leg is turned just slightly out, like he’s about to put his weight on it and get up. It’s no accident that the unseen light source falls on this leg.

The painting reminds viewers of a point central to central to Catholic doctrine: the existence of both God’s grace and free will. God’s grace calls us, but it is up to us to answer, to choose. Sara explained this was a point the church was especially eager to stress during the Counter-Reformation, because it opposed, for instance, Calvinist ideas of predestination. The hand of Jesus and the light of grace call Matthew, but they also call the pilgrims in the church, reminding them that salvation is freely given to all and they only have to choose it by following Christ.

As we made our way through Rome, Sara and our other art historian guides, Simona and Alberto, helped us do what Classical Pursuits always strives to do: Offer you, our travellers, rich and nuanced context of a time and place, but also encourage you to look! To look for yourself, deeply and closely, without preconceptions. Use what you see to form your own ideas, bring together everything you experience and learn in a way that is meaningful to you.

It’s hard to put into words the experience of standing before the many Caravaggio paintings we saw. I can still feel the emotions clearly: joy at the beautiful colours, shock at the dramatic action of Judith Beheading Holofernes (Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Antica, Rome), a deep heaviness as my eyes rested on the head of St. John, pressed to the floor (Beheading of St. John the Baptist, St. John’s Co-Cathedral, Malta). It was truly marvellous, and a trip I hope we will repeat.

But you don’t have to wait to have this kind of experience. Our next art trip is Slant of Light: Dutch and Flemish Old Masters in September 2022 to the Netherlands and Belgium, led by painter Sean Forester. Join us!

— Melanie

P.S. The JSTOR article I link to above is freely available, but if you don’t have a free JSTOR account you will need to create one to read the article.