[Editor’s note: We are thrilled to welcome Mandy Burton as a Toronto Pursuits leader. Her imaginative, multi-genre seminar will take us into realms both ancient and futuristic, where a cast of non-human characters helps us consider with piercing clarity those questions we as humans yearn so deeply to answer: Who are we? What should we do with our lives? Why does it matter?]

It is always a treat to return to a favourite work of fiction—but there is a peculiar, if somewhat estranging, pleasure in doing so in conversation with others. In the company of other readers I encounter the story anew, and feel both the intimacy of meeting an old friend and the challenge of encountering a delightful and startling stranger.

“Dolly,” by Elizabeth Bear, is an old friend of this kind. In this chilling little speculative-fiction detective story, a homicide detective begins to suspect that the murder weapon in her case—an advanced model “home companion” doll owned by the murder victim—may in fact be the murderer, and herself a victim of the very relationship she was built for. The story probes the connection between rights and desires, and explores the conditions under which we are prepared to recognize the humanity of others.

“Dolly,” by Elizabeth Bear, is an old friend of this kind. In this chilling little speculative-fiction detective story, a homicide detective begins to suspect that the murder weapon in her case—an advanced model “home companion” doll owned by the murder victim—may in fact be the murderer, and herself a victim of the very relationship she was built for. The story probes the connection between rights and desires, and explores the conditions under which we are prepared to recognize the humanity of others.

“Dolly” is one of the stories we will read and discuss together in my Toronto Pursuits seminar next summer. But—in part because I couldn’t wait until then—I also spent this past week talking about it with four classrooms full of computer science majors. The students in my computer science ethics course in Chicago have not necessarily chosen to be there: the course is a requirement for all CS majors, and the first few meetings typically have all the vim and vigor one associates with mandatory college graduation requirements. But that initial malaise evaporates pretty quickly once we move past ethical theory and into the science fiction worlds where the real work of the course transpires. To these technologists in training, who will soon be working in virtual reality or artificial intelligence or social media, “Dolly” and the other stories we read are windows into possible futures that they themselves might have a hand in building. The practical and moral crises drawn into relief by these stories could be the fruit of their own hands, or theirs to avert.

Until I began working with computer scientists, it had never occurred to me that the selling point of science fiction would be its practicality. The epistemology of the modern world, tilted as it is toward objective metrics and material outcomes, is not particularly favorable to literature, except as a source of pleasure. Science fiction and fantasy, in particular, are often dismissed as escapism: not particularly respectable, as pleasures go.

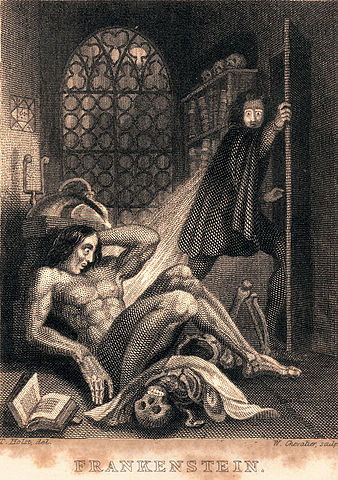

But literature has always seemed to me (and, of course, to many others) to be the most vital and trenchant—and yes, the most practical—way to ask foundational questions about who we are, and what we should do with our lives, and why it matters. One way in which literature can raise these questions is by clarifying our perception and understanding of what is familiar. Another way is by offering us a new and estranging lens on the familiar, enabling us to ask how and why the things we take for granted have come to be. Science fiction and fantasy—like the more ancient modes of storytelling they are heir to—are particularly well-suited to this sort of productive estrangement. The value of the enlarged landscape of these genres is not only to offer us radical new visions, but to help us turn our eyes afresh to the world of the familiar, and see it in a different way.

But literature has always seemed to me (and, of course, to many others) to be the most vital and trenchant—and yes, the most practical—way to ask foundational questions about who we are, and what we should do with our lives, and why it matters. One way in which literature can raise these questions is by clarifying our perception and understanding of what is familiar. Another way is by offering us a new and estranging lens on the familiar, enabling us to ask how and why the things we take for granted have come to be. Science fiction and fantasy—like the more ancient modes of storytelling they are heir to—are particularly well-suited to this sort of productive estrangement. The value of the enlarged landscape of these genres is not only to offer us radical new visions, but to help us turn our eyes afresh to the world of the familiar, and see it in a different way.

These inquiries into ourselves, and our role in the larger world, do not always bear tangible fruit that can be easily translated into economic value. But they are no less urgent for this: and that urgency can, perhaps, be understood even in terms of the practicality my students have been trained in. We are, after all, each of us makers and maintainers of our own selves, each a unique specimen of that most complex of machines, capable of acting to change the world around us. Of all the objects and all the futures that we might spend our time building, what matters more than this?

To learn more, read my interview with Melanie Blake at Classical Pursuits, Old Truths Made New.

I hope you’ll join me for Power, Rights and Personhood: Who Gets to Be Human?

– Mandy