Dickens’s last completed novel, Our Mutual Friend, is one of his most complex and ambitious works. It includes everything you’d expect from Dickens—a huge cast of characters, a convoluted plot, extremes of emotion, and a vivid depiction of life in Victorian London. (Did you know, for instance, that private “dustmen” in London picked up the refuse and presided over giant heaps of trash that had surprising value? You can find out all about it in this novel.) But the book also displays a profundity not present in most of Dickens’s earlier books.

Our Mutual Friend was written at a time of turmoil in Dickens’s personal and professional life. A series of wrenching experiences, ranging from an acrimonious divorce to a major railway accident, seem to have added shadows and depth to his work. I can’t list all the good reasons to read this novel, but here are my top five, counted down old-school David Letterman style until we get to number one.

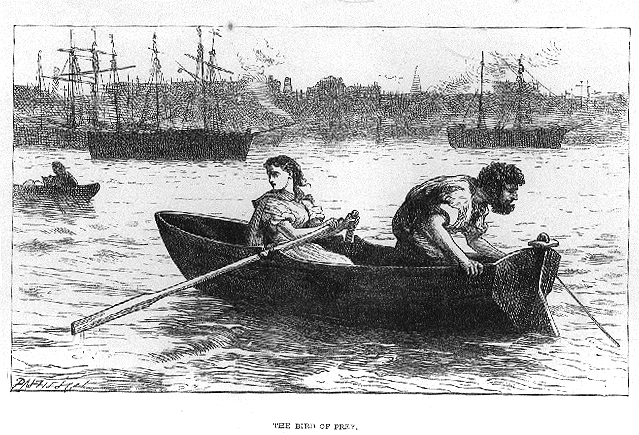

5. The portrait of the River Thames

In these times of ours, though concerning the exact year there is no need to be precise, a boat of dirty and disreputable appearance, with two figures in it, floated on the Thames, between Southwark bridge which is of iron, and London Bridge which is of stone, as an autumn evening was closing in.

In these times of ours, though concerning the exact year there is no need to be precise, a boat of dirty and disreputable appearance, with two figures in it, floated on the Thames, between Southwark bridge which is of iron, and London Bridge which is of stone, as an autumn evening was closing in.

From the novel’s first line, Dickens immerses us in the city’s great river. It becomes a physical symbol of the invisible connections between seemingly disparate characters, as well as the scene of rebirth and renewal. In his descriptions of the Thames, Dickens does some of his most emotionally evocative scene-painting. As you read about Rogue Riderhood pulling corpses from the Thames or Eugene Wrayburn’s near death in its waters, you will feel you are there.

4. The plots

“Mystery,” returns Wegg. “I don’t like it, Mr. Venus. I don’t like to have the life knocked out of former inhabitants of this house, in the gloomy dark, and not know who did it.”

A murder mystery, a suspenseful romance, a farce, a savage tale of social realism—it’s all here in Our Mutual Friend. Only Dickens can keep so many plots in motion, and through them build up the sense of a multifaceted, spinning world. Whatever genre you prefer, this novel has something to delight you.

3. The satire

Mr. and Mrs. Veneering were bran-new people in a bran-new house in a bran-new quarter of London. Everything about the Veneerings was spick and span new . . . . in the Veneering establishment, from the hall-chairs with the new coat of arms, to the grand pianoforte with the new action, and upstairs again to the new fire-escape, all things were in a state of high varnish and polish. And what was observable in the furniture, was observable in the Veneerings–the surface smelt a little too much of the workshop and was a trifle sticky.

Mr. and Mrs. Veneering were bran-new people in a bran-new house in a bran-new quarter of London. Everything about the Veneerings was spick and span new . . . . in the Veneering establishment, from the hall-chairs with the new coat of arms, to the grand pianoforte with the new action, and upstairs again to the new fire-escape, all things were in a state of high varnish and polish. And what was observable in the furniture, was observable in the Veneerings–the surface smelt a little too much of the workshop and was a trifle sticky.

In the Veneerings and the Podsnaps, Dickens developed his most complete portraits of social-climbing and buttoned-up respectability. The scenes featuring these characters are not only funny, but still relevant today. You’ll probably find that you have a Veneering or a Podsnap among your acquaintances.

2. The characters

Bradley Headstone, in his decent black coat and waistcoat, and his decent white shirt, and decent formal black tie, and decent pantaloons of pepper and salt, with his decent silver watch in his pocket and its decent hair-guard round his neck, looked a thoroughly decent young man of six-and-twenty . . . . Yet there was enough of what was animal, and of what was fiery (though smouldering), still visible in him, to suggest that if young Bradley Hadstone, when a pauper lad, had chanced to be told off for the sea, he would not have been the last man in a ship’s crew.

Bradley Headstone, in his decent black coat and waistcoat, and his decent white shirt, and decent formal black tie, and decent pantaloons of pepper and salt, with his decent silver watch in his pocket and its decent hair-guard round his neck, looked a thoroughly decent young man of six-and-twenty . . . . Yet there was enough of what was animal, and of what was fiery (though smouldering), still visible in him, to suggest that if young Bradley Hadstone, when a pauper lad, had chanced to be told off for the sea, he would not have been the last man in a ship’s crew.

Dickens creates some of his most affecting, and strangest, characters in Our Mutual Friend. Ranging from the broodingly repressed Bradley Headstone to the innocent “doll’s dressmaker” Jenny Wren, and including grotesques like the taxidermist Mr. Venus, once met these characters are unforgettable.

1. The questions

Mr. Inspector moved nothing but his eyes, as he now added, raising his voice . . . .

Mr. Inspector moved nothing but his eyes, as he now added, raising his voice . . . .

“You expected to identify, I am told, sir?”

“Yes.”

“HAVE you identified?”

“No. It’s a horrible sight. O! a horrible, horrible sight!”

“Who did you think it might have been?” asked Mr. Inspector. “Give us a description, sir. Perhaps we can help you.”

“No, no,” said the stranger, “it would be quite useless. Good-night.”

In Our Mutual Friend Dickens explores penetrating questions about identity, change, and what makes life worth living. How do you know who you are, or who anyone else is? Can people’s characters really alter? Who can you trust in a society seemingly dominated by the hunger for money, power, and position? Can love survive in such a hostile environment? Though Dickens sews up the plots, this novel leaves enough loose threads hanging that we, as readers, must make up our own minds about these issues. And that’s what brings me back to this novel again and again: whenever I reread it, it spurs me to think anew about what really matters.

You can click on the link to learn more about my seminar, “A Riddle Without an Answer”: Charles Dickens’s Our Mutual Friend. I’ll look forward to meeting you at Toronto Pursuits 2016!

– Nancy

Illustrations by Marcus Stone, scanned by Philip V. Allingham to the Victorian Web.