When my manager let me know that I would be spending a couple of weeks working on a project in Germany and the Netherlands, I admit that my first thoughts were not of reports and deadlines but of the Rijksmuseum. In the past several months I had been fortunate to see many magnificent Dutch and Flemish paintings on loan to San Francisco’s de Young Museum, the Seattle Art Museum, and New York City’s Frick Collection, but a visit to the newly reopened Rijksmuseum had seemed like a dream that would have to wait. Now, however, a chance had come to visit the museum, and with it the city that had attracted painters such as Ferdinand Bol, Barent Fabritius, and of course Rembrandt.

I delved deeper into my research on the Northern Renaissance and on Amsterdam’s rise as a major financial and cultural center and the world’s largest art market, following the story through the Low Countries and beyond. An idea took root in my mind. What better preparation for a visit to Amsterdam than a trip to Florence, the place of genesis for so many of the changes that brought Europe from the Middle Ages into modernity? The prospect of travelling from south to north and tracing through the visual arts the great flow of ideas of the Renaissance was too tempting an opportunity to pass up.

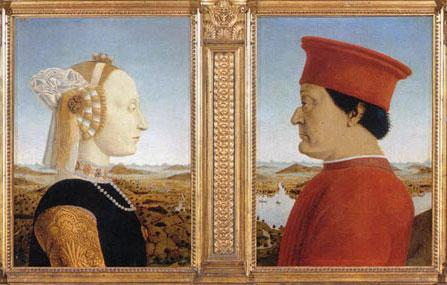

And so a few weeks later I found myself at the Uffizi, standing in front of Piero della Francesca’s portraits of the duke of Urbino, Federigo da Montefeltro, and his wife, Battista Sforza. The painting is a stop for groups on museum-organized tours, and the crowds file past the diptych exclaiming over the warts-and-all rendering of the duke and over Battista’s extreme pallor. (One guide dramatically announced that Battista was so pale and still-looking because she faced her husband from beyond the grave. She died in 1472 and although some sources suggest the diptych was commissioned after her death, the Uffizi’s own website says della Francesca began work in 1465.)

The groups filed past, leaving me to study the painting. In many ways this work of modest dimensions (each portrait is 47 × 33 cm) symbolized the daunting nature of what I was trying to do with my crash course on Renaissance art. The double portrait before me and the paintings of the Dutch Golden Age at the Rijksmuseum were separated by 200 years and 1,400 kilometers. The time and space between them were not connected in a linear way, with ideas simply radiating out of central Italy to other cities and regions as the years passed. Della Francesca’s diptych can be seen as a classic example of a new style of portraiture that prioritized realistic detail and psychological depth more than medieval portraits had done. From the start, however, della Francesca and other Italian artists such as Domenico Ghirlandaio were absorbing and responding to the work of peers in Flanders and elsewhere. Della Francesca’s faithful recording of the duke’s broken nose and his handling of the bird’s-eye view of the landscape owe a great deal to Flemish art.

These aspects of the painting were just two small threads in a vast web of connections, influences, and allusions. Over the next few days I visited the Duomo, Santa Croce, Santa Maria Novella, and a few smaller gems, my favorite of which was Santa Felicità, one of the oldest churches in Florence and a treasure that I had missed on previous visits to the city. In each place I tried to be open to perceiving how artists interacted with and interpreted the past and one another’s work. There were so many beautiful things to look at that it was hard not to try to get to it all, but as I moved through Florence and then made my way north, I made a strong effort to slow down and really see what was around me. I wanted to keep the pattern formed by these visual connections intact, and not have it become a random tangle.

The best thing about my trip was that there were so many opportunities to absorb and appreciate works of art both for themselves and in a larger context. The most obvious way to do this was simply by being there—reading about Brunelleschi’s understanding of balance and proportion is a different experience from actually standing in the Pazzi Chapel. To be able to get close and study the impasto Rembrandt used in The Jewish Bride or the way Michael Sweerts painted Joseph Deutz’s sleeve in his portrait of the young man is often as close to a tactile experience as we can have while looking at art.

Watching other people’s experiences also yields insights. One person I saw was visibly disgusted by Titian’s Venus of Urbino, but just about everyone seemed delighted by the freshness of the frescoes in Santa Croce. What do people notice or overlook? What are they commenting on, and which details are they compelled to sketch or photograph?

Of course, curators also foster these connections by the way they arrange a gallery. In the Rijksmuseum I was happy to discover a whole room on Dutch painters in Italy. In the new Gallery of Honor, Rembrandt’s masterpiece The Night Watch (1642) is surrounded by two other large portraits of militia companies on the side walls. This arrangement gives visitors a chance to look at three large-scale compositions to compare and contrast. The other two are more traditional militia portraits, where the groups are standing and posing rather than getting ready, as in Rembrandt’s portrait. They look a bit like friezes and, to my mind, the juxtaposition of the three works helps viewers better understand Kenneth Clark’s argument for the “high Renaissance basis of Rembrandt’s composition,” (1) with its foreshortened central group and second plane where there is lots of activity.

For me, there is one more piece that ties it all together. Especially when looking at more intimate portraits of one or two people, I like to think about the story behind each painting. Going back to della Francesa, a viewer might notice that Federigo looks quite a bit older than Battista, and indeed he was 24 years her senior. He was a condottiero, or a mercenary captain, and she took over responsibility of his territories in his absence. She was highly educated and literate in Latin. They apparently had a very happy marriage, with one contemporary describing them as “two souls in one body” (2). Any viewer would be hard-pressed to find this sentiment in della Francesca’s portraits, and of course he was not painting them to show a loving marriage. In contrast, about 200 years later with The Jewish Bride (c. 1665), Rembrandt uses gesture and expression to paint a portrait of love that is at once so powerful and tender. It is impossible not to share in the couple’s quiet joy.

The expression on Rembrandt’s face in his Self-portrait as the Apostle Paul is harder to read. The self-portrait was also painted later in Rembrandt’s career (1661) following many years of personal and financial struggle. The 1640s saw the death of Rembrandt’s wife, his later casting aside of his lover Geertje, her possible blackmail of him, and his subsequent (and successful) efforts to have her committed to an asylum. These events were followed by his bankruptcy and the sale of his huge art collection.

The man in this painting has suffered, and he has caused others to suffer. What is he trying to tell us about himself, what he has experienced, and what he has done? Scholars know little about Rembrandt’s religious beliefs; why did he choose to represent himself as Paul? As I studied his eyes and face, the penultimate line of Paul’s letter to the Corinthians came to mind: “For now we see through a glass, darkly; but then face to face: now I know in part; but then shall I know even as also I am known.” I had come to the end of my journey and had travelled far, from the earliest innovations of Ciambue and Giotto to these nuanced portraits in Amsterdam that look back and invite or even challenge us to know them.

People create, possess, study, admire, and love art for such a variety of reasons. Most are noble, a few less so. I like to think that among the most important of these reasons are to see our world a little less darkly; to better know and interact with our emotions, ourselves, and each other; and to participate however we can in the creation of beauty.

1. Kenneth Clark, Rembrandt and the Italian Renaissance, NYU Press, 1966, p. 85.

2. http://www.kleio.org/de/geschichte/begegnungen/bild013.html

Thanks to Jen Loebsack, photographer extraordinaire, for the bicycle photo.

Melanie last wrote about the Classical Pursuits 2013 trip to Paris. She did not cycle all the way from Florence to Amsterdam, but she will someday!