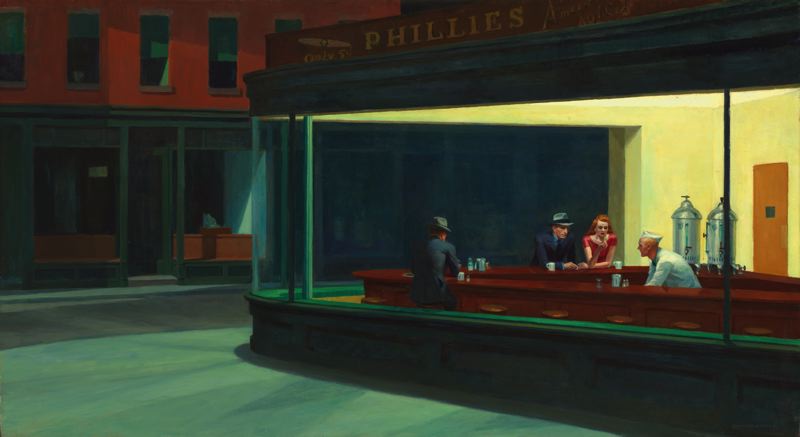

The man on the left sits solitary. The bartender seems to be speaking, but no one responds (the woman looks at what she is holding in her hand, and the man seems to be lost in his own thoughts). Edward Hopper’s Nighthawks creates a powerful atmosphere, a feeling of melancholy. The composition – with a large empty space on the left side and electric light against a dark street – reinforces the mood.

In contrast, let’s consider a painting from the Gilded Age, Dorothea and Francesca by the great portrait painter Cecilia Beaux. Beaux shows a mother and daughter, hand in hand, striding forward. Although the both look down, the feeling to me is one of tenderness and connection. This is emphasized by the lines which hold the picture together. It is a triangle composition, but the bottom is a graceful curve that goes from the girl’s hand through the lifted dresses to her mother’s hand then up her arm to her head. On the way down, the eyes descends a series of steps: face, hands, face, hand.

The paintings at the Art Institute of Chicago give us an opportunity to explore the theme of solitude and connection. Love and friendship are central to our happiness, yet we also need space for solitude and reflection. We are social creatures. Still, we can feel lonely in a crowd or even when we are touching another person. These paradoxes may not have easy answers, but they can be explored and illuminated through art.

Beaux’s contemporary, Mary Cassatt, also has a painting of a mother and child in the Art Institute. This work is more about pattern than tone; I believe it shows the influence of Japanese prints. How would you describe the connection between mother and child in Cassatt’s piece compared to Beaux’s?

Moving from motherhood to marriage, we turn to Sargent’s The Fountain, Villa Torionia, Frascati, Italy, which shows an artist painting a man leaning on a balustrade in front of a waterfall. This is one of my favourite paintings in the museum.

It is a virtuoso performance of imposts, dry brush work, and varying tones and colours within the whites: impressionistic yet drawn with great precision. This is why Sargent is described as a painter’s painter. But what about the relationship between the two figures? They are a young couple, Jane and Wilfred von Glehn, both artists. Jane describes the painting in one of her letters, “Sargent is doing a most amusing … picture in oil of me sitting on a balustrade painting. It is the very ‘spit’ of me. He has stuck Wilfred in looking at my sketch with a rather contemptuous expression … I am all in white with a white painting blouse and a pale blue veil around my hat … I have rather a worried expression as every painter should have who is not a perfect fool, says Sargent.” The painting is an interesting peak into the relationship of two creative people.

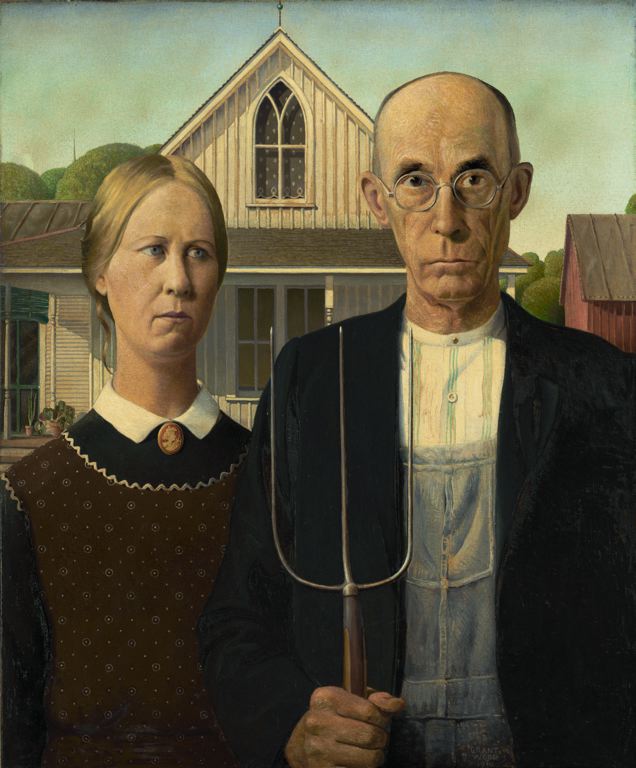

Finally, another icon, Grant Wood’s American Gothic. What is the relationship of the two figures here?

I look forward to hearing your answer when you join Gary Schoepfel, Ann Kirkland, and me in Chicago, May 2-6. We will explore the Institute’s permanent collection and the special exhibitions that are on view this spring: They Seek a City: Chicago and the Art of Migration, 1910-1950, and Picasso and Chicago. But we will not only be, so to speak, “reading” paintings. There will also be architecture, literature, and music. We will have a great time Reading Chicago.

See you there!

Sean Forester

Founder, Golden Gate Atelier